I want to talk to you now about the role museums play in producing and reproducing ‘knowledge’ of the past and how they contribute to a particular view of society with reference to the Tate Modern as a site of discursive practice.

The key idea of ‘discursive practices’ is that they must contain rules1 which define and separate 'truth' from 'falsity'. Museums in general do this by narrating a story in the present about the past according to a particular set of 'rules' which attempt to render a story 'true'. Museums have a great amount of control over what gets to be exhibited and how it is displayed.

Our ability (not quite the right word) to challenge their authority can be explained in a couple of ways.

Firstly, in the way that museums themselves are products of a particular time and space. Museums emerged in the geographical so-called 'West' and are usually viewed as places in which objects of historical, artistic, or scientific interest are exhibited and preserved. This location in the west has had an effect on the way the museums' buildings are designed, on what they hold and on the kind of visitor they attract.

The Tate Modern originally had as its aim to be a place to define and safeguard heritage. This was the mission statement of most museums. As places that held categorised collections of exotic antiquities and curiosities brought back from the civilising missions of European colonialists, museums definitely could be accused of orientalising the other. So, these items and the way they were displayed told us much more about the ideology of the society in which the museum is than where the objects came from. Objects are taken out of their original context and re-embedded within an artificial environment which in itself contributes to the type of myth that is told.

The second way in which authority is exercised is through the control of visitor behaviour by the design of the building. In Discipline and Punish Foucault discusses the concept of prisons being designed along the lines of an all-seeing eye which demands respect and not to be questioned. He was not so much saying that all prisons were designed like this but that the panopticon concept embodies a new way of controlling society and therefore a new conception of society.

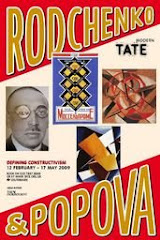

Slide: Rodchenko ‘s big brother

These ideas of a new society can also be seen in the way museums discipline visitor behaviour. Visitors behaviour, for example, is controlled by the way objects are displayed, by the stories they tell and also by the design of the building itself. Often referred to resemble temples or places of religious worship they enact upon the visitor a sense of awe and reverence for the objects but also for an unquestioned past. With objects being kept out of reach visitors are only to passively observe and accept the story they are being told; there is no chance for dialogue between the visitors and the objects. And the visitor does all this largely unaware of the ideological pressures being put on them.

Show slide/blog on the Sun exhibition.

Quote: by the artist Jake Chapman ‘You feel very small in the face of magnitude of this cathedral. It sends messages for miles: this is important, this is a sacred place, everything here is sacred. Things that are sacred are not questioned and that’s the problem’

In this exhibition behaviour is further modified by a number of things. In permanent exhibitions the visitor is free to wander around and absorb information in their own time. Temporary ones though are usually accompanied by an entrance fee (although entrance is free to people who can afford membership), a time-allocated entry slot, a strictly narrated sequence of objects and assumption of a prior, if not indepth, knowledge of art history.

The curator Margarita Tupitsyn exhibitions put together the exhibition based on two artists-one male, one female. This to me is a deliberate attempt to reinforce the fact that gender equality was an important communist ideal. Rodchenko’s wife was a major artist in her own right but by choosing to exhibit Popova the curator is emphasising how female artists were being taken as seriously as male ones for the first time. The extent to which the movement managed to challenge previous sexist inequality…?

Timeline.

conclusion

The extent to Popova maintained

What we know about the past can only be a representation.

Panopticism. We have given the museum to…narrate.

Time-line as the myth of history progressing and reducing the diffuse artists into categories which can be rationalised and can then become absorbed into a body of art knowledge.

The fact that you have to go past it reinforces their authority as the narrators of art history and authors of knowledge.

Production and reproduction of knowledge.

Reviews.

Panopticon.

The Tate modern itself is ‘a story brimming with symbols’.

Thursday, 30 April 2009

Constructivism comes from the Russian Konstruktor which means: ‘the one who constructs’

So in Russian ‘constructivism’ is synonymous with engineering1.

The engineer is concerned with the production of utilitarian objects and in this case these utilitarian objects are propaganda based on scientific principles.

The word construction in English looses this close association with engineering.

Images were constructed using the compass and ruler;

Emotional and stylistic qualities were seen as obsolete – in an essay called ‘The Line’ Rodchenko describes the brush as an insufficient and imprecise instrument that could be surpassed by the ruler and ruling pen;

In this sense scientific rational principles were used in opposition to traditional forms of artistry which relied on inspiration2; different brush strokes were rejected in favour of ‘The Line’; and traditional artistic skills were rejected in favour of mass propaganda.

In short this is the rationalisation of the creative processes and impulses and art education was governed based on scientific principles designed to teach the artist to produce predictable and measurable effects in the viewer. (SLIDE 1)

Kandinsky was the first president of INKhUK (the Institute for Artistic Culture).

He drew up a catalogue which documented the psychological effects of foundational visual elements.

The Institute then established a psychological laboratory in mid 1920 to further develop these ideas and it produced a ‘dictionary of visual effectiveness’.

This was the development of a ‘science of art’, exerting an organising influence on the psyche by means of emotional control of the perceptions.

For instance the whole range of colours, shapes and elemental forms were systematically measured according to their psychological effect, and this study was based on scientific work dating from at least since the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

These concepts were to be disseminated by artists.

Tretykov, head of the VKhUTEMAS, explains that the revolution had put forward a new practical task for artists whereby they were required by the state to ‘affect mass psyche and to organise the will of the classes’.

In 1921 the Institute for Artistic Culture engaged in a discussion about how to turn artists into constructivists or engineers. They were taught how to use modern engineering methods based on the rigorous scientific study of the human psyche, industrial design and mass propaganda intended to scientifically control the perceptions of the masses.

Originally visual works contained measurable and calculated simple forms, but gradually they became to be composed only of these aspects.

Rodchenko, for instance, describes the reduction of painting to its logical conclusion- a common sentiment based on an evolutionary telos. (SLIDE 2)

The ruler and compass represent the mathematical systematic use of simple form. Geometric forms were therefore ideal for controlling response in the viewer, the imagery itself being based on (at least) decades of investigation into the psychology of perception and scientific aesthetics.

In the 1920’s Soviet Russia aimed to create a mass psychological culture, 3 it was one of the most extreme behaviourist experiments to be so openly and rigorously scientifically documented and was designed not just to control consumer habits (as in the west), but also to systematically engineer and control the consciousness of the whole society.

Apart from the Institute for Artistic Culture there were a number of psychological labs set up in various art institutions such as the VKLUTEMAS, GAKLN and the State Institute of Artistic Culture.

Their goal was the ‘fully rationalised visual language of mass communication’ whereby ‘each element was capable of communicating a meaning, producing an emotion and causing a behavioural response’4 (SLIDE 3)

Rodchenko developed a visual language whereby each elemental abstract form would produce a completely predictable response in the audience.

Under his presidency the Institute for Artistic Culture pursued a systematic study of the ways in which the masses could be controlled through perception of visual form5.

Art was to be the ‘organisation of life’6, (SLIDE 4) and the bringing of ‘Art into Life’ (SLIDE 5) was articulated by using three dimensional designs and effecting the ‘flow of the crowds’ by using architecture based on geometrical form.

What was being engineered? (SLIDE 6)

The Institute for Artistic Culture tells us that it is the psycho physical human consciousness7 that is being engineered.

Architecture, mass spectacles, posters, designs, photomontages etc were designed to produce ‘calculated bodily responses, emotions and meanings in the viewer’8

To shape the human being as an organised unit9 under a single State authority.

The goal was the development a new society. This new society could only progress or change if the individual units of the whole were altered. Therefore to transform the society the state had to manage the behaviour of the individual, hence the emphasis on scientific behaviourism, sexless and geometric working clothes (SLIDE 7) and standardised architectural designs for buildings etc.

This is always based on an evolutionary model whereby diversity is reduced to unity and fixity, and individual different apperceptions of form are reduced to standardised norms.

In this sense artistic inspiration, expression and individuality etc became standardised by means of the compass and rule, number and line.

References:

Lodder, C (1983) Russian Constructivism.

All INKhUK quotes from Manovich, L (??) The Engineering of Vision: From Constructivism to Computers

The Tate Modern: Rodchenko and Popova: Defining Contructivism

1 Monivich p.156

2 Manovich p.156

3 Manovich p.23

4 Manovich p. 8

5 Manovich p.153

6 Lodder p.109

7 Versin at INKhUK

8 Manovich p.156

9 INKhUK – ‘Engineerism’

So in Russian ‘constructivism’ is synonymous with engineering1.

The engineer is concerned with the production of utilitarian objects and in this case these utilitarian objects are propaganda based on scientific principles.

The word construction in English looses this close association with engineering.

Images were constructed using the compass and ruler;

Emotional and stylistic qualities were seen as obsolete – in an essay called ‘The Line’ Rodchenko describes the brush as an insufficient and imprecise instrument that could be surpassed by the ruler and ruling pen;

In this sense scientific rational principles were used in opposition to traditional forms of artistry which relied on inspiration2; different brush strokes were rejected in favour of ‘The Line’; and traditional artistic skills were rejected in favour of mass propaganda.

In short this is the rationalisation of the creative processes and impulses and art education was governed based on scientific principles designed to teach the artist to produce predictable and measurable effects in the viewer. (SLIDE 1)

Kandinsky was the first president of INKhUK (the Institute for Artistic Culture).

He drew up a catalogue which documented the psychological effects of foundational visual elements.

The Institute then established a psychological laboratory in mid 1920 to further develop these ideas and it produced a ‘dictionary of visual effectiveness’.

This was the development of a ‘science of art’, exerting an organising influence on the psyche by means of emotional control of the perceptions.

For instance the whole range of colours, shapes and elemental forms were systematically measured according to their psychological effect, and this study was based on scientific work dating from at least since the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

These concepts were to be disseminated by artists.

Tretykov, head of the VKhUTEMAS, explains that the revolution had put forward a new practical task for artists whereby they were required by the state to ‘affect mass psyche and to organise the will of the classes’.

In 1921 the Institute for Artistic Culture engaged in a discussion about how to turn artists into constructivists or engineers. They were taught how to use modern engineering methods based on the rigorous scientific study of the human psyche, industrial design and mass propaganda intended to scientifically control the perceptions of the masses.

Originally visual works contained measurable and calculated simple forms, but gradually they became to be composed only of these aspects.

Rodchenko, for instance, describes the reduction of painting to its logical conclusion- a common sentiment based on an evolutionary telos. (SLIDE 2)

The ruler and compass represent the mathematical systematic use of simple form. Geometric forms were therefore ideal for controlling response in the viewer, the imagery itself being based on (at least) decades of investigation into the psychology of perception and scientific aesthetics.

In the 1920’s Soviet Russia aimed to create a mass psychological culture, 3 it was one of the most extreme behaviourist experiments to be so openly and rigorously scientifically documented and was designed not just to control consumer habits (as in the west), but also to systematically engineer and control the consciousness of the whole society.

Apart from the Institute for Artistic Culture there were a number of psychological labs set up in various art institutions such as the VKLUTEMAS, GAKLN and the State Institute of Artistic Culture.

Their goal was the ‘fully rationalised visual language of mass communication’ whereby ‘each element was capable of communicating a meaning, producing an emotion and causing a behavioural response’4 (SLIDE 3)

Rodchenko developed a visual language whereby each elemental abstract form would produce a completely predictable response in the audience.

Under his presidency the Institute for Artistic Culture pursued a systematic study of the ways in which the masses could be controlled through perception of visual form5.

Art was to be the ‘organisation of life’6, (SLIDE 4) and the bringing of ‘Art into Life’ (SLIDE 5) was articulated by using three dimensional designs and effecting the ‘flow of the crowds’ by using architecture based on geometrical form.

What was being engineered? (SLIDE 6)

The Institute for Artistic Culture tells us that it is the psycho physical human consciousness7 that is being engineered.

Architecture, mass spectacles, posters, designs, photomontages etc were designed to produce ‘calculated bodily responses, emotions and meanings in the viewer’8

To shape the human being as an organised unit9 under a single State authority.

The goal was the development a new society. This new society could only progress or change if the individual units of the whole were altered. Therefore to transform the society the state had to manage the behaviour of the individual, hence the emphasis on scientific behaviourism, sexless and geometric working clothes (SLIDE 7) and standardised architectural designs for buildings etc.

This is always based on an evolutionary model whereby diversity is reduced to unity and fixity, and individual different apperceptions of form are reduced to standardised norms.

In this sense artistic inspiration, expression and individuality etc became standardised by means of the compass and rule, number and line.

References:

Lodder, C (1983) Russian Constructivism.

All INKhUK quotes from Manovich, L (??) The Engineering of Vision: From Constructivism to Computers

The Tate Modern: Rodchenko and Popova: Defining Contructivism

1 Monivich p.156

2 Manovich p.156

3 Manovich p.23

4 Manovich p. 8

5 Manovich p.153

6 Lodder p.109

7 Versin at INKhUK

8 Manovich p.156

9 INKhUK – ‘Engineerism’

Greg's presentation

Myth presentation-- Rodchenko and Popova, Russia constructivism and the state

** Slide 1- title page**

The Russia revolution of 1917 saw the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy in February of that year, with the Bolsheviks eventually managing to seize power in the October. The Bolsheviks proceeded to establish the world’s first communist state. This event is regarded by many as one of the most consequential events of the twentieth century, proving, as it did, an inspiration for revolutions in other countries such as China, as well as influencing, or provoking, the rise of Fascism in Europe and, after 1945, providing the foil against which the West defined itself, as well as, along with the West, drawing, or re-drawing the architecture of foreign policy and international relations and interventions.

The conception of progress conceived the Bolsheviks was greatly indebted to Enlightenment ideals, reflected in their belief that the dissemination of knowledge and rationality would liberate people from their superstitious and backward ways, and lead to an enhanced freedom and autonomy. They aimed to do this by raising the level of 'culturedness' of Russian society, which at the time was conceived as being steeped in 'Asiatic' backwardness. By 1921, once they had gained victory on both the political and military fronts, culture was declared the 'third front' of the revolution, or revolutionary activity. This development of 'culturedness' included carrying out ones trade union duties efficiently, punctuality and cleanliness, and literacy. Lenin proposed the concept of 'cultural revolution' as a vital stage in the development of the country towards socialism, within the framework of Marx's historical determinism.

Other Bolsheviks, such as Bukharin, promoted a more radical conception of what Cultural Revolution could and should be. He asserted that it should be a: 'revolution in human characteristics, in habits, in feelings, and desires, in way of life and culture'. As such, his aim was the creation of a 'new soviet person' through a total transformation of daily life.

** Slide 2 **

The art movement known as 'constructivism' accompanied the Russian revolution, with the first use of the term being a reference to the work of Alexander Rodchenko. The movement aimed to question the fundamental properties of what art is, what art can be, and what its place should be within the new kind of society they saw emerge. The ideological concept behind the movement was to produce art forms that could contribute to everyday life. This conception mirrors that of Bukharin, whereby art, in the form of painting, architecture, design, film, as well as every-day objects, could be used to advance the revolution, and ultimately transform the every-day life of the people, creating a new culture, and eventually the 'new soviet person' conceived by Bukharin.

In the early years after the revolution, artists sought to re-invent art starting from zero. This involved the rejection of ideas of illusory representation, limiting the paintings of Rodchenko as well as Popova to geometrical patterns, with an emphasis on the relationship between textures and colours. This reflects their conception of the artist as engineer, and the production of the art object as not dissimilar to that of any other manufacturing process, which as such, was seen as in keeping with the ideals of the revolution by casting the artist as a worker like any other. In May 1920, the research institute and think-tank INKhUK was founded as a forum for the discussion of the principles that should underline modern art.

Ultimately it was decided that the medium of painting was irreconcilable both with their approach and aesthetic, as well as with their ideology. Their final exhibition, 5 x 5 = 25, which opened in September 1921 was their farewell, the works exhibited included a piece by Popova constructed of straight lines and triangles, as well as Redshank’s famous triptych of three canvases in each of the primary colours, affirming that 'every plane is a plane and there is to be no representation'.

With the advent of Lenin's New Economic Policy, or NEP, which allowed private enterprise to operate on a limited scale, the constructivists were employed to create the advertising for state run industries facing new competition; they were also involved in the production of posters for propaganda and education, including histories of the Bolshevik party. Here we can see the increasing role played by the artist in narrating a history and society, based on the Marxist determinist model of progress, about and for the newly enfranchised poor and uneducated masses.

** Slide 3 **

With the ultimate goal being the creation of a new cultural paradigm for the new kind of individual, with the cultural revolution involving revolutions in the forms of desires, feelings and ways of life, both Popova and Rodchenko moved into the implementation of this cultural revolution by changing the conditions of every-day life, these included in particular, fabric designs and costume designs by Popova, as well as cigarette packets and utilitarian clothes by Rodchenko. This move to designing everyday objects reflects the Marxist conception of the base structure, in the form of the conditions of everyday life, is reflected in the superstructure, which includes politics and ideology, and as such was a core tool for the construction and narration of the myth of Marx's determinist model of historical progress.

Points of debate:

The contemporary use in advertising and design of constructivist inspired aesthetic; what does it mean today? A signifier of defiance and revolution? How is it used and exploited by advertising design etc. to sell products and create a narrative around the kind of person that buys and consumes these products. Tapping in to the popular imagination.

Dichotomy between revolutionary and proletariat art?

** Slide 1- title page**

The Russia revolution of 1917 saw the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy in February of that year, with the Bolsheviks eventually managing to seize power in the October. The Bolsheviks proceeded to establish the world’s first communist state. This event is regarded by many as one of the most consequential events of the twentieth century, proving, as it did, an inspiration for revolutions in other countries such as China, as well as influencing, or provoking, the rise of Fascism in Europe and, after 1945, providing the foil against which the West defined itself, as well as, along with the West, drawing, or re-drawing the architecture of foreign policy and international relations and interventions.

The conception of progress conceived the Bolsheviks was greatly indebted to Enlightenment ideals, reflected in their belief that the dissemination of knowledge and rationality would liberate people from their superstitious and backward ways, and lead to an enhanced freedom and autonomy. They aimed to do this by raising the level of 'culturedness' of Russian society, which at the time was conceived as being steeped in 'Asiatic' backwardness. By 1921, once they had gained victory on both the political and military fronts, culture was declared the 'third front' of the revolution, or revolutionary activity. This development of 'culturedness' included carrying out ones trade union duties efficiently, punctuality and cleanliness, and literacy. Lenin proposed the concept of 'cultural revolution' as a vital stage in the development of the country towards socialism, within the framework of Marx's historical determinism.

Other Bolsheviks, such as Bukharin, promoted a more radical conception of what Cultural Revolution could and should be. He asserted that it should be a: 'revolution in human characteristics, in habits, in feelings, and desires, in way of life and culture'. As such, his aim was the creation of a 'new soviet person' through a total transformation of daily life.

** Slide 2 **

The art movement known as 'constructivism' accompanied the Russian revolution, with the first use of the term being a reference to the work of Alexander Rodchenko. The movement aimed to question the fundamental properties of what art is, what art can be, and what its place should be within the new kind of society they saw emerge. The ideological concept behind the movement was to produce art forms that could contribute to everyday life. This conception mirrors that of Bukharin, whereby art, in the form of painting, architecture, design, film, as well as every-day objects, could be used to advance the revolution, and ultimately transform the every-day life of the people, creating a new culture, and eventually the 'new soviet person' conceived by Bukharin.

In the early years after the revolution, artists sought to re-invent art starting from zero. This involved the rejection of ideas of illusory representation, limiting the paintings of Rodchenko as well as Popova to geometrical patterns, with an emphasis on the relationship between textures and colours. This reflects their conception of the artist as engineer, and the production of the art object as not dissimilar to that of any other manufacturing process, which as such, was seen as in keeping with the ideals of the revolution by casting the artist as a worker like any other. In May 1920, the research institute and think-tank INKhUK was founded as a forum for the discussion of the principles that should underline modern art.

Ultimately it was decided that the medium of painting was irreconcilable both with their approach and aesthetic, as well as with their ideology. Their final exhibition, 5 x 5 = 25, which opened in September 1921 was their farewell, the works exhibited included a piece by Popova constructed of straight lines and triangles, as well as Redshank’s famous triptych of three canvases in each of the primary colours, affirming that 'every plane is a plane and there is to be no representation'.

With the advent of Lenin's New Economic Policy, or NEP, which allowed private enterprise to operate on a limited scale, the constructivists were employed to create the advertising for state run industries facing new competition; they were also involved in the production of posters for propaganda and education, including histories of the Bolshevik party. Here we can see the increasing role played by the artist in narrating a history and society, based on the Marxist determinist model of progress, about and for the newly enfranchised poor and uneducated masses.

** Slide 3 **

With the ultimate goal being the creation of a new cultural paradigm for the new kind of individual, with the cultural revolution involving revolutions in the forms of desires, feelings and ways of life, both Popova and Rodchenko moved into the implementation of this cultural revolution by changing the conditions of every-day life, these included in particular, fabric designs and costume designs by Popova, as well as cigarette packets and utilitarian clothes by Rodchenko. This move to designing everyday objects reflects the Marxist conception of the base structure, in the form of the conditions of everyday life, is reflected in the superstructure, which includes politics and ideology, and as such was a core tool for the construction and narration of the myth of Marx's determinist model of historical progress.

Points of debate:

The contemporary use in advertising and design of constructivist inspired aesthetic; what does it mean today? A signifier of defiance and revolution? How is it used and exploited by advertising design etc. to sell products and create a narrative around the kind of person that buys and consumes these products. Tapping in to the popular imagination.

Dichotomy between revolutionary and proletariat art?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)